Week 3 of the Alphabet Sufficiency: A. I’m just late this week. I’ll probably have some commentary on that at some point.

I saw the solar eclipse in November, or at least the right half of it, and thus began a six month dabbling in general relativity. It all started innocently enough, looking at astronomy websites to learn about, eg, why there isn’t a solar eclipse every month, which isn’t a relativity question at all..

Since New Moon occurs every 29 1/2 days, you might think that we should have a solar eclipse about once a month. Unfortunately, this doesn’t happen because the Moon’s orbit around Earth is tilted 5 degrees to Earth’s orbit around the Sun. As a result, the Moon’s shadow usually misses Earth as it passes above or below our planet at New Moon. At least twice a year, the geometry lines up just right so that some part of the Moon’s shadow falls on Earth’s surface and an eclipse of the Sun is seen from that region.

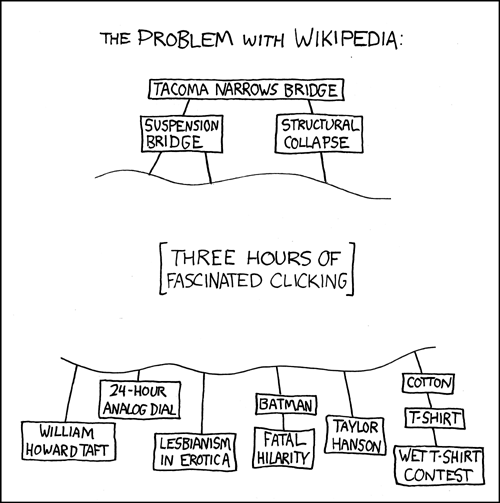

Well that’s that answered, but I’d made the mistake of visiting Wikipedia, and we all know how Wikipedia works:

xkcd: The Problem With Wikipedia

Or actually, we don’t quite, because Randall Munroe apparently uses Wikipedia differently from me. If I end up on Wikipedia, I won’t be spread out among William Howard Taft and wet t-shirt contests, I will be in one of two places: poisons, or black holes. I can’t explain the poisons thing either, but black holes are pretty self-explanatory: relativity! spacetime! breaks down! infinite density! spagettification! gamma ray jets!

Or you can get your poisons and your black holes in the one place:

A supernova or hypernova produced by Eta Carinae would probably eject a gamma ray burst (GRB) out from both polar areas of its rotational axis. Calculations show that the deposited energy of such a GRB striking the Earth’s atmosphere would be equivalent to one kiloton of TNT per square kilometer over the entire hemisphere facing the star, with ionizing radiation depositing ten times the lethal whole body dose to the surface.

Eta Carinae, one of the most massive star systems in the Milky Way, is 7500 light years away. So, imagine that: a radiation jet so powerful that it would deliver lethal radiation doses to us across thousands of light years, if we happened to lie in the path of the axis of rotation at the time of a supernova. Which, luckily, we probably don’t.

I thought, in high school, that I’d be a physicist one day. I read the popular works of Stephen Hawking and Richard Feynman and Paul Davies. In Year 11 and 12, when NSW high school students only take English as a compulsory subject and all else is elective, I loaded up with maths, physics and chemistry. When I went to National Youth Science Forum, I asked to be placed in one of the groups for students most interested in physics. I went to the International Science School for high school students (not especially international, I might add) and poured over the pictures of physics PhDs and postdocs imagining myself among them.

And then various things happened and I’m not a physicist. I didn’t even take university physics in my first year. One of those things was a poor assignment of teacher in Year 11 physics: it was hard to dent my academic performance in high school but possible to dent my academic enthusiasms. Another of those things were that I had a lot of trouble with the intuitions of classical mechanics, especially of tension, and found myself regurgitating definitions by rote to get the right answer, and I had a lot of choices of subjects where I didn’t have to do that. (I hit similar walls with chemistry in first year university and mathematics in second and third year. Probably, like with physics, a break of a decade or two would have helped a lot: I revisited classical mechanics over a few hours with Andrew’s help about four years ago and now I know that in the idealised situations we were dealing with, the ropes and strings are rigid. Such simple things. I might be a scientist now if I’d had more age-peers.)

I don’t even especially regret this, I think my passion for physics was more a passion for strange phenomena than a passion for making novel discoveries of strange phenomena. I’m still not especially good at telling the difference between things I want to research and things I want to read about.

I imagine this isn’t an uncommon way to view one’s personal history, but I feel like I straddled two major technological transitions just as I reached adulthood. The first is the ubiquity of mobile phones: when I started university in 1999, rich kids had them. When I returned for my second year, everyone had them. The second is the Web. I remember writing reports in primary school—if allowed to choose my topic, they’d either be on astronomy or on the human brain—relying on the local library. Which to be fair, was information dense enough for me at the time.

But that’s not how I answer my questions now. Seeing the solar eclipse, meant lots of wiki walks and Google queries that ended in black holes, or at least quite near them. And frankly, for the first time ever, I started to feel like the Internet might be too close to being my mind, externalised, only with more answers. I don’t need to exert effort, I can just mainline facts. I am generally suspicious of “information diet” kind of sentiments: I usually analyse them as in part an aesthetic or moral preference for having to do labour, which I don’t think is justifiable in and of itself. Neither simplicity nor labour are in my opinion a good thing, they’re just means to ends. But… obviously I partake of the culture that creates these ideas and frankly, it’s a little spooky that there’s entire sections of the Internet set up to teach people who are apparently just like me in terms of background knowledge (some) and willingness to do work (little) about black holes and general relativity.

I had better justify the use of the ‘acceleration’ topic first:

In the physics of general relativity, the equivalence principle is any of several related concepts dealing with the equivalence of gravitational and inertial mass, and to Albert Einstein’s observation that the gravitational “force” as experienced locally while standing on a massive body (such as the Earth) is actually the same as the pseudo-force experienced by an observer in a non-inertial (accelerated) frame of reference.

And so I will spend my acceleration efforts on general relativity and gravity. You see why you need to be comfortable in your own intellectual laziness on the Internet these days, don’t you?

It’s probably fairly obvious how one gets from solar eclipses to black holes, but for the record, I believe it was via a bunch of reading about solar astronomy, with a detour through Wikipedia: Health threat from cosmic rays. You don’t spend long on cosmic rays before you end up considering this baby:

The Oh-My-God particle was an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray (most likely a proton) detected on the evening of 15 October 1991… Its observation was a shock to astrophysicists, who estimated its energy to be approximately 300 exa-electron volts (3×1020 eV or 50 J)[1]—in other words, a subatomic particle with kinetic energy equal to that of a 5-ounce (142 g) baseball traveling at about 100 kilometers per hour (60 mph).

Wikipedia: Oh-My-God particle (see also xkcd what-if?)

And from there, you’re pretty much considering what happens if Eta Carinae goes supernova. And secretly worrying that whatever the quantum gravity prediction is is less cool than general relativity. Which it probably will be. I own my aesthetic preferences, and they are on Einstein’s side.

After that the true recognition that there are thousands and thousands of people on the Internet really established itself. Every time I thought of a question about black holes, there was some ancient FAQ (1995? dawww) that answered them.

First, ones that had puzzled me for a while. There’s extreme time dilation around black holes from the point of view of a sufficiently distant observer: do they therefore see me hovering around the black hole forever? Do I see the entire universe flash before my eyes before my time is up?

I had assumed the answers were yes and yes, but they’re actually no and no, at least if you stick to Schwarzschild black holes as more ore less everyone does. Matt McIrvin sorts this out pretty much back-to-back in his FAQ:

Won’t it take forever for you to fall in? Won’t it take forever for the black hole to even form?

Not in any useful sense. The time I experience before I hit the event horizon, and even until I hit the singularity—the “proper time” calculated by using Schwarzschild’s metric on my worldline—is finite. The same goes for the collapsing star; if I somehow stood on the surface of the star as it became a black hole, I would experience the star’s demise in a finite time…

Now, this led early on to an image of a black hole as a strange sort of suspended-animation object, a “frozen star” with immobilized falling debris and gedankenexperiment astronauts hanging above it in eternally slowing precipitation. This is, however, not what you’d see. The reason is that as things get closer to the event horizon, they also get dimmer. Light from them is redshifted and dimmed, and if one considers that light is actually made up of discrete photons, the time of escape of the last photon is actually finite, and not very large. So things would wink out as they got close, including the dying star, and the name “black hole” is justified.

As an example, take [an] eight-solar-mass black hole… If you start timing from the moment the you see the object half a Schwarzschild radius away from the event horizon, the light will dim exponentially from that point on with a characteristic time of about 0.2 milliseconds, and the time of the last photon is about a hundredth of a second later. The times scale proportionally to the mass of the black hole. If I jump into a black hole, I don’t remain visible for long…

Will you see the universe end?

If an external observer sees me slow down asymptotically as I fall, it might seem reasonable that I’d see the universe speed up asymptotically—that I’d see the universe end in a spectacular flash as I went through the horizon. This isn’t the case, though. What an external observer sees depends on what light does after I emit it. What I see, however, depends on what light does before it gets to me. And there’s no way that light from future events far away can get to me. Faraway events in the arbitrarily distant future never end up on my “past light-cone,” the surface made of light rays that get to me at a given time.

Fine then, answer all my questions. After reading that I huffed over to Google and typed in “does gravity move at the speed of light?” just to see whether the Internet is all it is cracked up to be. And a different section of the same damned FAQ actually answers this more or less in that form. Actually the answer is kind of cool: general relativity predicts that the distortions that gravity creates in spacetime propagate at the speed of light, yes, but in such a way that in most cases the source appears to be the instantaneous location of the massive object. Which is in turn super-lucky because otherwise you don’t get remotely stable orbits. Which as I recall resulted in a breather at Wikipedia: Anthropic principle but I was willing to fight on for a bit.

I wasn’t done, because I had encountered brief mentions of an interesting property of black hole event horizons, which is that inside the event horizon, one dimension of space becomes timelike, which can be informally considered as “the singularity is in your future”. I kept talking excitedly to Andrew about this late at night, I think when I was supposed to be working on something else (often cooking dinner) and the more I talked, the more I realised that I had absolutely no idea what this really meant. This required actual work on my part in terms of poking at Google queries, but luckily for this project, not very much, and it wasn’t long before I ended up at Jim Haldenwang’s Spacetime Geometry Inside a Black Hole which breaks out mathematics, and is worth a read in full. In addition to some of the mathematics, including that property of event horizons, it talks a bit about the historical development of the understanding of black holes, including the fact that the event horizon was also a singularity in the original coordinate system and it took more than thirty years to show that in some coordinate systems, it isn’t.

Frankly, I remain a little horrified at how little work I had to do to find any of this out. No overdue library books? No interacting with knowledgeable humans in real time? Some time in my 20s the future appears to have arrived with a vengeance, as it so often does. Outside of black holes, anyway.