Three moments of 2022

Not dozing in the sun in Munich airport. We flew from Sydney to Rīga via Singapore and Munich, and both transits were terrible, Singapore because it was the middle of the night and Munich because we wanted it to be and it very much wasn’t. But Munich airport has plastic lounge chairs in the airport and we lounged on them in bright summer sun pouring in through huge windows, allegedly fixing our body clocks, or at least, being awake.

Wandering in a daze of pain through Muir Woods. I went to Muir Woods twice this year, on both trips to the Bay Area. The second time I had some kind of digestive upset and ended up in a slightly altered state of consciousness, torn between pain and the somewhat meditiative experience that is inherent to Muir Woods.

Carrying a couch up our street in breaks between rain. We rented office space (former therapy rooms, in fact) near our home in 2021 in order to have a place to work that wasn’t also doubling as a school and 24/7 nuclear family circle of hell. I found it hard to let go of the lease before winter was over since it was difficult to imagine a winter without society closing down.

And then I tore my MCL skiing — the opposite of that kind of winter — and it was hard to give up the lease because I couldn’t help move the furniture out of it. Finally, with the historic spring rains, it was time, and the couch was the last thing out, moved to our porch for a freebie pickup just ahead of a forecast downpour.

Three meals of 2022

Georgian food at Alaverdi, gruzīnu restorāns, in Rīga. Mostly I remember cheese dipped in honey, and wine, and the fact that it was 10pm and not yet sunset.

Smoked pork on rye bread, bread pudding, pickled cabbage various colours, honey vodka among other parts of our food tour of the Rīga Central Market. It started inauspiciously with the guide being (only a little late), but then she was thrilled to meet Australians (“they let you out!” “people from Australia and New Zealand are Latvia’s best tourists!”) and even our picky child was moderately pleased with the idea of an afternoon snack of pork and bread.

Fish at Doyle’s at sunset. I’ve lived in Sydney for 24 years and there’s still a raft of fundamental Sydney things I haven’t done, this was this year’s. The sunset is the key, more than the fish.

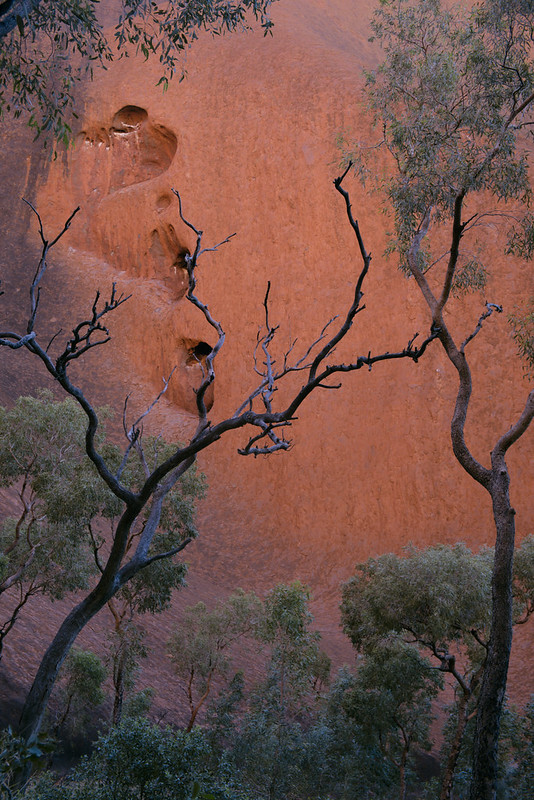

Three photos of 2022

Three pleasures of 2022

Mid-childhood. My children are nearly 9 and 13, They were never not people, but at this stage being a kid of a particular age is a less dominant part of their identity than being particularly themselves. So we have cricket that approaches a part-time job in its commitment level, 5:30am starts to get to cheerleading, sketches in advance of a future fashion label, and someone unexpectedly installing chess apps on their phone alongside TikTok.

Certainty. I haven’t had to tell anyone that their holidays or school or surgery aren’t happening or are delayed or are being replaced with some rushed together home equivalent. I skipped only one family event myself due to illness/contagiousness.

A welcome summer. It rained so much this year and has been so cool that the moderately warm summer days of late December have been quite welcome and joyful, rather than the harbringer of unpleasantness it can be in many years. Watching the sunset from Milk Beach on Christmas Day while a group danced to salsa music from someone’s phone; the morning of New Year’s Eve supervising pre-teen girls squealing in the gentle surf at Wattamolla. Beautiful.

Three news stories from 2022

A year of pundits being terribly wrong about the biggest of big stories. Putin won’t invade Ukraine (Atlantic Council, BBC, Al-Jazeera, University of Melbourne), China will not exit zero COVID (Time, the Atlantic, Bloomberg).

Apparently our former Prime Minister was formerly several other ministers too. The point I, and many others, return to a lot, is “but, also, why?” This is yet to be satisfactorily explained.

Two and a half metres of rain for Sydney. Someone I know lost a friend in the regional flooding.

Three sensations from 2022

Fatigue-and-pain hour. I had COVID at the end of January, it felt like being the last person to get it, but the seroprevalence surveys put me only in the first 40% or so of Australians. Overall I’d put it at worse than most colds, better than influenza, and certainly much better than that time I had early sepsis (which is quite the barometer for bad illness). Its tendency over about the next two weeks to show up arbitrarily once a day for about an hour at a time, fatigue-and-pain hour, was the most distinct part of it.

A plane rocketing down a runway ahead of taking off. Twelve times altogether I suppose but I most distinctly remember the first one leaving Sydney for San Francisco in March, 772 days since my previous plane flight in February of 2020.

The dim shape of chairlifts in the clouds. Our first day in Falls Creek in August was a windy whiteout — they evacuated the mountain at lunchtime — and my daughter gamely skiied down a run with me with neither of us having skied in two years. I was motivated mostly to keep the chairlift in sight for reference rather than find an easy slope and so was very proud of her fortitude.

Three sadnesses of 2022

Tech layoffs and the associated rumour mills, churn, and anxiety. It’s been especially hard since the economic boom that immediately proceeded it was very much a money-boom; during that period folks were sick, sad, and isolated, and do not have an emotional boom-time worth of resilience.

Relatedly, the mid-career exit of women I know in tech continues apace.

Sulking at a hotel window view of Falls Creek’s Summit area during the “walking is very uneasy and requires a lot of planning” phase of my MCL injury. A very winter sport moment, but I had finally found an instructor to sort out my parallel turns this time for sure, just long enough for me to catch the wrong edge ahead of the end of week bluebird days, and it was frustrating.

Three plans for 2023

Both types of NSW beach road trip, that is, north and south, and both in the next four weeks. We booked the southern one, back to the same town where we holidayed in 2019, 2021, and 2022, some of my family booked in to meet us there, and then my son was invited to play in a cricket carnival about as far in the opposite direction as is possible. So, northern cricket tournament first, unpack cricket gear, wash remainder of clothes, head south.

SCUBA. The big hobby of our 20s, but early mornings and babysitters made it so unappealing in our 30s. We’re hoping to dive off Byron Bay, which I have wanted to do for at least 15 years. I don’t think going back to 20 dives a year is on the cards, but, I plan to do a handful of them.

Falls Creek re-run. 2022 was our first extended family ski trip, we stayed in a local family’s hotel full of regulars, with a communal lounge and a babysitting and dining for kids, and of such are family traditions made.

Three hopes for 2023

A narrative of my career that makes sense. My career isn’t bad — it’s highly paid and I get good reviews — but its current iteration is very formed by “just get through this crisis and then” where “this crisis” refers to at least four completely distinct events over three years at this point. A sustainable narrative is what I want.

North American winter, a year from now. I wanted to do this the year my son was 10, it somehow seemed like the perfect age. That year was 2020, so, we did not. I don’t dread the flights or the prices less after Europe in 2022; this may be a case of wanting to want something. But I’ve wanted to want it for a long time!

Catch up on my photography backlog. I’m almost, but not quite, three years behind. I’m not ready to give up. It’s a lot, but there’s a lot of beauty and memories in there that I want access to.