April 2022

Some of these are among my favourite photos I’ve ever taken.

by Mary

In March 2020 my family began supporting the Haymarket Foundation, a secular charity for people experiencing homelessness and disadvantage. We’re particularly supportive of their work on complex homeslessness, and their trans inclusive crisis housing.

We’ve continued supporting them since, and this winter we are matching your donations to the Haymarket Foundation, supporting residents like Deo Nuyu, a refugee from Burundi, who cannot access income support without a protection visa, to remain housed. Volunteer Vic, who recovered from drug abuse with the help of the Haymarket Foundation, credits their case workers with the difference in his life.

My family and I are matching donations to the Haymarket Foundation up until June 30, give today to support homeless and disadvantaged people in Sydney!

Wishing a child luck when leaving them in an anaesthetic bay. My children are too old now for me to detail their medical status publicly, but this year featured a major surgery, of which we had had mere hints at New Year, but by February had reached “I’ve cleared my list on Tuesday” urgency. And so.

Coughing so hard that my boss’s boss told me to go and get a drink of water. Every COVID wave this year (both of them) was marked with me getting a rubbish and seemingly non-COVID chest infection. My winter one saw me getting at least three separate PCRs trying to ensure I wouldn’t be spreading COVID at the vaccine clinic and then left me with months long choking coughing fits. The meeting with my boss’s boss was just before I started using Ventolin to manage the coughing, which I needed for a further month.

Sunset at Milk Beach, more than 5km from home and therefore near and then beyond the bounds of the possible. / “Sunrise” at The Gap the day that restriction was lifted, and the clouds and misty rain were far too thick for the dawn to be seen.

Self-saucing chocolate puddings from a giant pack of cooking-with-fancy-chocolate guides that my aunt sent at the beginning of Sydney’s lockdown (lots of sympathy inbound in the six weeks or so it took for the lockdown to spread outside the metro region). Hot and incredibly filling.

Enormous fish tacos for Mexican Friday at one of my local bars. It was just a lot of taco!

Bennelong again, as we wanted to go there again and sit in the main restaurant after Andrew’s 40th. One of the rare times I don’t remember the actual food well (possibly I ordered the duck?) but the occasion. We had cocktails at Maybe Sammy prior, which I remember rather better: gin, and huge cubes of clear ice.

My parents’ beautiful farm. I was confined to Sydney by health order for four months and then caught in the whirl of rebooting my life, so we didn’t visit between Easter and Christmas. It has rained immensely, all the teenage trees from the first years of their ownership are thickening and even the ancient established gums look fatter. The steers can’t be seen in the tall grass and the lawn is springy and needs mowing most days.

All the ways that my children aren’t like me. For example, flexibility is very important to A. She can do the splits in every axis and one of her lockdown skills (they’ve happened enough that she believes that a “lockdown skill” is a sort of fact of life) was one handed cartwheels on both sides.

A commute. I had to rent it; I have office space near my house. But 2 minutes of space between me and the morning chaos at home has made a huge difference to my mornings, when most of my important and high stakes conversations take place. Now, behind a door that locks.

The missing children who were found: “they found AJ Elfalak!” “they found Cleo Smith!”

French-Australian diplomatic tensions over the cancellation of a submarine order. This is memorable mostly because of the number of times I girded myself to finally, properly, understand whether the level of resentment was justified, and the number of explainers I diligently began reading only to realise at the third paragraph that eyes moving back and forth does not constitute reading things in and of itself. Bouncing off a news story so hard is itself memorable.

Gladys Berejiklian’s resignation as NSW Premier. I rarely watch things like this (I can’t stand to watch concession speeches at election time), but I had spent months watching her 11am winter COVID wave press conferences with Kerry Chant and others most days, following bushfire press conferences a year and a half before, and so somehow had to be there for the end as well.

The inevitable sore arm from three COVID vaccinations and counting. A funny tasting headache with it, just on the edge of perhaps being imaginary.

Walking backwards off a cliff, abseiling on our camping trip. I hadn’t abseiled as an adult and expected this to be extremely confronting, but the best way to walk backwards off a cliff is to do it nice and fast, and to jump as much as you can. On a slightly harder course, I ended up smacking into the cliff and needing to do a minor self rescue before flying over a cave in one bound.

Being squashed by V, now reaching an adult weight, once the lockdown grumps had abated a bit. And the view of the top of his head, all the other times he believed that lying face down next to me constituted a hug.

The narrowing vision around the pandemic. The world shuddered at the Indian disaster, and then you had to look carefully to catch the Tunisian and Indonesian disasters, the latter particularly a repeat of India. This has been happening since March 2020, but getting worse, the pandemic horizon gets smaller all the time.

This last few years, whatever horrible sympathetic magic happens to parents about tragedies and children set in for me, and so, I spent days in hazes of horror after the Werribee house fire (recalling the Singleton fire of 2019) and the jumping castle tragedy in Davenport.

The tail end of Sydney’s lockdown and the re-entry were very hard on my kids. Not easily distinguishable from age-appropriate grumping at times, but with some distance; a lot of it was the lockdown.

Wall-to-wall travel, apparently.

Beach holiday, why not try this again? We were in the end able to head down the coast last year in January for our bushfire/pandemic-deferred beach holiday, and we have booked another one at end of this January. Even more so than last year, it’s a long time away in public policy terms.

Uluru. As the Australian border opened, I was musing on trying to put together a trip to Japan for their spring, but got lost in a maze of their restrictions, our restrictions, and incoming immune-evasion variants. Then I saw Peter Carroll’s photography of Uluru in the rain (via some non-crediting Twitterer who will therefore remain unlinked) and we booked a Uluru trip for autumn instead.

I have never seen Australia’s deserts before. I have no expectation it will rain.

Family snow trip. We got really close, one family got as near as having the car packed before the government pulled the plug; 2021 was the first year we’ve missed since 2013.

Andrew and I have better gear to make up for our deficiencies, V is keen to try snowboarding, A is way more adventurous than she used to be, and also has nearly a year of acrobat muscle built up. This could be our year.

Had to work to avoid wall-to-wall travel.

Visiting the US. This has at least been legal for me to do for a month (and I was invited to do so almost the second it was), quite when I will consider it either useful (other people need to be at the office) or sensible I am not sure of. 2022 is the hope, perhaps even early in the year.

Roadtripping Highway 1 with Andrew seems a bit much to hope for within the year.

Sailing in Queensland. This is a repeat hope, but eastern Australian border closures seem finally done for with pan/endemic COVID everywhere. Springtime nights under the moon on a catamaran, I’ve been trying to get this together for nearly four years. “Hopefully by spring…”

A full year of schooling. It’s been about five months of virtual schooling in two years, somewhere between the US and many European countries. It’s been enough and more.

October 2021

The 11th was the date when NSW stopped having a 5km travel limit, so I left home before sunrise and drove to The Gap to watch the first far-from-home dawn.

Of course, it was damp and cloudy and dark, no dawn to be seen. There’s more variety in the transforms on the photos than I usually do, because the light was so average.

It was great.

March & April 2020

I was looking through my phone photo detritus from the time of the original closures (which were not as strict as the July to October 2021 ones, during which I mostly stuck to photographing sunsets rather than sign-of-the-times images).

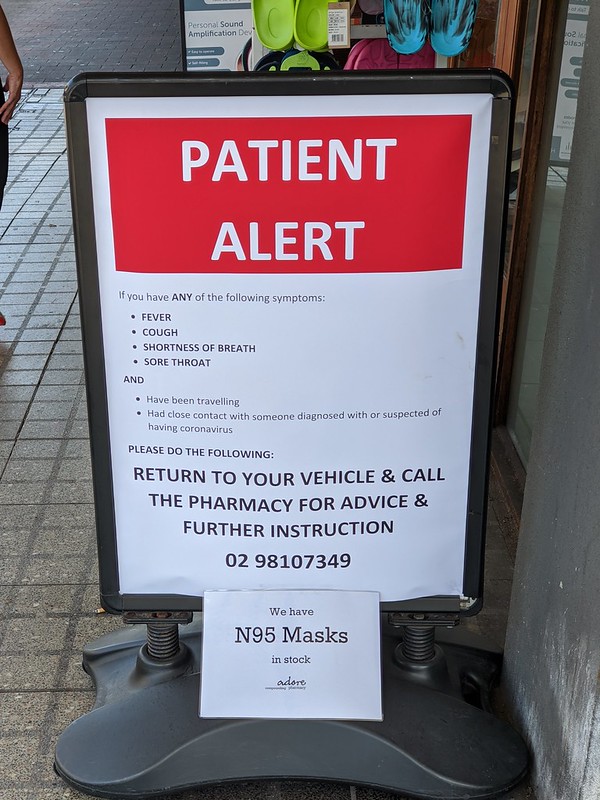

Early on, this kind of sign was unusual enough that I photographed it especially:

I never figured out if the placement of a hand hygiene sign next to a cheap will preparation sign was deliberate, and if so, intended to be funny, shocking, or just attention-getting:

Speaking of bleak, we played one game of Pandemic but it got awfully real with outbreaks in East Asia and Russia:

Our local Flight Centre was lookng forward to welcoming us back for several months. It closed permanently nearly a year ago now:

I’ve never been to a ANZAC Day dawn ceremony in my life, but I did happen to be awake at dawn, so went and stood in my yard as was the style at the time.

Someone somewhere was audibly playing The Last Post.

August 2021

Watching the sun set from within my Sydney travel boundary somehow became a symbol of interstate rivalry. May it return to coffee soon.

Previously: Milk Beach.